Like many Indians of my generation, I was left with my maternal grandparents for the early years of my childhood. Traditionally in India children were often watched by their grandparents. But as more parents seized opportunities to find jobs in cities or immigrate to other countries, they left young children with relatives for longer periods. We – the kids who were left behind – were the accepted casualties of such “progress”. My early life in India was productive albeit traumatizing, in so far as I learned how to curse well in Malayalam by yelling insults over the tall concrete wall that separated our small house from the school for delinquent boys. I grieve for the hardness and aloneness of that tough little girl and the grown woman. I grieve for my lack of mothering, of fathering. And I grieve because later, a steady intake of McDonald’s “happy meals” were often the closest I got to “happy” as a little adorable, oblivious immigrant kid in the suburbs of America. When, as a non-English speaking little 5-year old, I was dropped off at Kindergarten by my parents in the mornings, I would ask them in Malayalam, “Will you come pick me up today like you picked me up the other day? Promise me you will.”

What being left had meant is that several things were always in question, several assumptions on Maslow’s basic needs hierarchy were never givens. What’s wrong with me that they left me? Why am I not good enough? (This is true for a lot of us even if we had our parents around. And, the fact is having your parents around doesn’t necessarily make life much better, as I would eventually come to know.) Yet the part that wants to bank on survival is also always at odds with the part that’s angry at having been left, as well as the part that’s in grief about the abandonment. Underlying all has been the belief that I will surely get left again, because love equals abandonment. Every subsequent relationship and heartbreak then brings forth these same questions. I often felt like I was branded by a scarlet letter “A” for Abandonment. Can they all tell I’m damaged goods— that was left behind?

I’ve spent my entire life making whole this rupture in my soul. I’m 39 years old now. I’ve had to work at it from several angles, and I believe all those angles are each important, valid, sacred, and that one is not a substitute for the other. There is the work of coming to feel the ground of the earth as that Mother presence who never left me, who never will leave, as well as the sense of an essential Father presence who always loved me as well, and who truly wants the best for me. There is the work of coming to know myself as essentially good enough, as loved, as loveable, and as one who doesn’t deserve to be abandoned by another, for something or someone else. There is the work of grieving, which is actually woven into every other work as well. This grief – the anguish of being left – opens the doorway to all the other grief in our world, all that’s ever been grieved or still needs to be grieved. It cracks all the way down into the bone into our shared heart. My experience of having been left is a fragment of that of all who’ve been left, all who’ve had to leave, all who feel homeless and alone in this world – past and present. My abandonment is what’s allowed me to feel at home in this world, when finally, as an adult, I began to see that so few of us are really at home here at all – most are just very good at pretending. Most of all, it’s what’s allowed me the gift and burden of feeling: deeply, profoundly.

I love Rumi’s line, “Pain bears like cure like a child.” Only the child can know the pain of being left at a young age. Even though it was a gentler way of being left than so much of what happens in our world, to the child it’s still excruciating. The terror of not having your mother’s breast near, her voice, your father’s hands. Of not being able to walk, or talk. Only cry. And cry and cry you did until by and by, they found ways to distract you, and you found ways to keep yourself busy. But that sadness never went away. It became a sort of familiar plaster in my soul where the rupture happened. Sadness became my signature. It’s easy to become addicted to the wound. Until I could begin to see, and then admit: “I am not only that.” My little girl wound holds the medicine I need, and the medicine I have to offer the world. Good medicine, bitter medicine— that lets me taste the sweetness of life.

The other work then, is that of re-telling. I am a storyteller. The work of any real storyteller is to tell a story in the most whole way possible. It’s coming to see that the story possesses its own eloquence, and to not leave out the details. I “got” only recently, that those opportunities my parents wanted for me could only honestly have come about this way, (even though to their chagrin, I haven’t become a doctor, lawyer or engineer!) Who I am now is the product of growing up in India as a toddler speaking one language fluently, and then being an uprooted immigrant in the U.S. learning English, which is now my primary language. Who I am is because I’ve never belonged to any one place or people. If I’d not grown up on a mono-diet of Coca Cola, sugar and television, I wouldn’t now be this woman who works to dismantle notions of “first-world progress” that are still devouring her “third-world” homeland. I wouldn’t have become the woman who hitchhiked around America alone, or bicycled through villages in Kerala, or who creates site-specific ritual performances. I wouldn’t have been the woman who had to return to India again and again in order to learn how to tell stories, and how to carry the seeds her ancestors saved – to keep them alive and bring them from destruction in her home country – here to this not all-together-friendly and foreign place.

None of who I’ve become would’ve been possible if not for the sacrifice my parents made in leaving me. I think of my breast-feeding mother, heavy and swollen with milk as she boarded that plane for the first time to a country that would treat her like any other immigrant – stupid, substandard, at best exoticized – she, having held her daughter for the last time in several years. I think of my father, his somber grief hiding the ungrieved grief of his childhood, the tender boy who was beaten up by his own parents daily, who would grow up to be a man too sensitive for this world, who – like most everyone else – had to learn how to numb himself from an early age. Such leaving is a kind of sacrifice you live out slowly through the estrangement from your only child – in wondering nights if you did the right thing, knowing that you did the only thing that made sense to do – waiting for that day you would bring her back to you as months turned into years, only to have her eventually hate you for the very sacrifice you made so she could become who she was meant to be. Only a parent can know what it is to have to leave a child.

When my mother finally came to get me in Kerala, she looked like a dazzling Hollywood celebrity with her American clothes and sunglasses. Apparently I had excitedly told my mother’s sister who was mu substitute mother, “my mom – my amma – is coming to get me, and she is sooo pretty!” I remember my trip to the US on the plane – how she saved a biscuit for me while I was asleep, and how much that meant to me. I know that for me, for us, there were no accidents. Just the shaping of lives by forces beyond our control, our comprehension— making us who we are, how we are, why we are: beautiful, misshapen, poetically storied people.

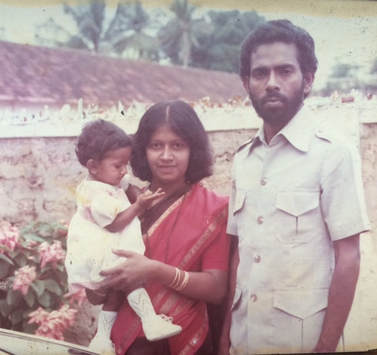

A few years ago, I had the immediate and visceral realization for the first time in my adult life, that my parents wouldn’t be here forever. That they might actually die sooner than I imagine. That all my years of resenting, hating and separating myself from their own pain-inflicting wounds would be nullified, and I would truly and finally be “alone.” When our parents leave this earth, that is the ultimate in feeling “left”. They just won’t be here anymore. That night, I cried knowing I hadn’t told my parents how much I actually loved them, how much I was grateful to them, that I knew how much I must worry them just by being who I am. I saw that my parents had once been young people and that now they were old and at the close of their own lives. I didn’t want them to die yet. No not yet! I searched frantically then- for a photograph of the three of us in India. It’s a photo that I always imagined was taken the day they left me. Later, when I showed them this photo, my mother couldn’t remember; she said she hadn’t worn that sari on the plane. I imagine my mother on the plane again— her milk-laden breasts then nursing the rows of carefully wrapped colored glass bangles that perched precariously on her lap throughout the whole trip, my father beside her anxious and expectant making miscellaneous reports about everything in and outside the plane; their serious young faces – like in the photo – trying to not let on about the loss they knew was inevitable, as they were propelled hundreds of miles an hour into a future that was unknowable.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed